Keep it Simple

A Series on Beginning DevOps /part five

This is the fifth part in a six part series on Beginning DevOps, and follows Where to Start?

Self Service is Key

We’re talking about DevOps, which means that every team ultimately becomes responsible for its own stuff. The talented and increasingly skilled individuals that you brought together to develop, deploy, and operate the tooling are going to get bogged down so fast if they turn in to a service organization supporting each one of your developers. That’s not DevOps.

Facilitate Easy Adoption and Empowerment

Think about how you can keep the learning curve as short and shallow as possible. If you ask someone to read thirty pages of text in order to gain enough knowledge to hand-build their first pipeline, then you’ve already lost.

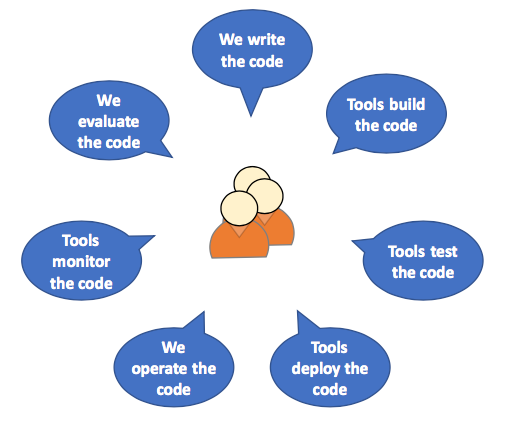

At the end of the day, each team needs to be able to work fairly independently in harmony with the tooling, like this:

One thing that really helped us was the institution of template repos: clone this thing and you’ll have a “Hello World” application that will build, deploy and run. It was a revolutionary way to change the conversation from “I can’t make it work” to “what changed that might have broken it”. In hindsight, it’s probably something I’d have given higher priority to had I known how much time it would save.

The simpler you can make this cycle for people, the smoother everyone’s life will be!

The Tools Aren’t Everything

Although the conversation starts with tooling, it’s vital to consider this as a cultural/people/organizational conversation, and it’s important to keep that front-of-field as you get deeper into the problem space.

The tooling is there to eliminate silos and permit developers to get feedback faster, and the more benefit that they can gain from this the better. But ultimately, we’re there for the benefit of the developers so that they — in turn — can deliver value faster to the business.

To this end, it’s important not to get lost in perfection, or iterating on technology faster than is necessary (but also make sure that you don’t get too far behind).

Concisely Document as You Go

You don’t need to document APIs (after all, that’s what Swagger is for), and a lot of the other stuff should be either dynamically built or live in a repo.

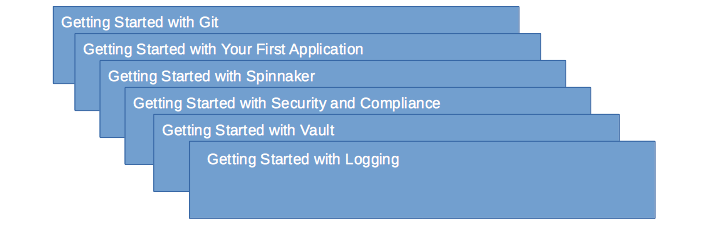

Sadly, though, your developers will need help. As we got into it, we created a set of Confluence pages that covered things like:

…and so on. Going back to the whole multi-modal thing, we also had a set of video demos and presentations that new hires could work their way through. Of course, this didn’t happen overnight, but we did our best to keep up as new features were added, and as common questions appeared in our Slack channels.

But there’s more than end-user documentation: we also made sure that we had easy reference to AWS accounts, CIDR block ranges, and other handy (but not super confidential) information.

Compromise on Features, not Stability… or Technical Debt

When we set out on our path in 2015, Spinnaker was still limited to the folks at Netflix, and we had to make do with Asgard. It kinda got us where we needed to be in the short term, and the benefits of learning and enabling developers to self-service deployments was totally worth the do-over work that we knew we’d have to deal with later.

Having said that, make sure that you’re conscious of any technical debt that you’re taking on, and you’re using that debt wisely: There are parallels between technical debt and financial debt in that they both accrue interest if not managed, and it’s better to avoid having to stall other work for months as you work out how to dig yourself out of that hole. Make sure that you have a pay-back plan.

Although it’s sometimes okay to incur technical debt in the short term, the same can’t be said for stability. Never compromise on stability, although don’t over engineer: think of the number of consumers of your systems, and how many developers a bug or outage can affect. Think then what the impact to the value stream might be to the business and lost opportunity cost. People are counting on you for this stuff to work, and I bet your team wants to get paged in the middle of the night just as much as the next person.

Really, Really, Keep it Simple

As a junior software developer, I was keen to show my prowess around writing “clever” snippets of code. Even before that was a time when something was “good” if it basically just worked.

The trouble is that you (or others) will find it hard to understand later. So it’s important to code in a simple, clean, and clear manner.

Don’t Let Perfect Be the Enemy of the Good

A lot of what we do is experimentation and learning. We know that we won’t get it right first try, and that’s okay. DevOps gives us the opportunity to fail fast, learn lessons, and evolve.

The Cult of Done Manifesto might overstate it slightly, but be pragmatic about what you work on. Maybe you don’t need all of those features right now, or maybe you can quickly reduce the number of potential solutions to two or three out of an initial set of ten. Above all, don’t get caught by Analysis Paralysis.

Continuously Monitor and Evaluate

How is your build infrastructure scaling? How many commits on how many pipelined repos are there, and how far down the pipeline does each commit make it? How many artifacts are you storing? What are your various API rates? How much money are you spending on each category of cloud infrastructure, and how well is that infrastructure utilized? How far have you come since you started?

You get the idea.

This is essential to driving conversations with the development teams about whether they really need that cluster of eight m5.4xlarge EC2 instances, each with just 0.5% utilization.

It also helps limit surprises when deployments begin failing because the infrastructure has reached an API limit, or to ensure that your team — just like everyone else — can be an effective custodian of the services and infrastructure in your care. As an aside, the API limit thing can take some tracking down, and can cause all sorts of weird symptoms as we found to our detriment.

Abstraction: The Unsung Hero

As adoption of the tooling grew, so did our general level of smugness. At some point, though, we realized that a few of the assumptions we’d made were wrong, and the degree of complexity required to express configuration on others had changed and required refactoring.

The unfortunate consequence of this was that certain aspects of developer’s repos had to change, and we had two choices: either we could make those changes on the behalf of developers, or we had to keep track of progress toward change completion so that we could decommission the old way of doing things. Either way, these required a burden of attention on our part, and distracted us from working on the next big thing.

We realized fairly late in the game that if we’d done things differently with interface points into our tooling (for example standard library for JobDSL, or a common end point for logging), then we could have changed things without anyone even caring.

If you do this right, developers will see the tooling “just work” and won’t think a second of it. But you’ll know, and your team will be more productive. That’s enough.

Maximize Homogeneity: Cattle not Cats

Over time, it’s likely that a development team will come to you and ask for a specific feature, or perhaps they’ll tell their boss that they’re blocked waiting on you for that feature.

It can be really tempting to extend the tooling to support their specific use case. But that may be a mistake.

It’s important to keep the tooling as simple as possible, and guide design decisions around new applications to maintain a high level of ubiquity. The reason for this is simple: the more special cases you have to manage, the more complex the infrastructure (that will take longer for newcomers to learn), the harder it becomes to upgrade, and the more things that can go wrong.

The more that you can drive towards common solutions and tooling that are widely used, the simpler your infrastructure will be, and the cost of maintenance will stay relatively contained.

This means things like:

Just one operating system (and one version) for Linux-based deployments

Just two framework and language versions (leading and lagging) for the foundational packages that sit between the OS and an application

Reuse pipeline tooling wherever possible and modularize across deployment target types (such as serverless, containers, etc.)

Where a feature can be widely adopted across the organization (and that does happen), then figure out how to integrate it with your existing tooling in a clean and modular fashion, refactoring as necessary.

Build, Buy, or Adopt?

It’s an old question, and it’s not always as easy to answer. It’s common to think that the challenges in your organization are unique, but the truth of the matter is that more often than not, someone has already blazed the trail and invested a ton of energy in to coming up with something that not only already does the job, but has already been adopted by a community. Always ask yourself “should we build it?”, rather than “can we build it?”.

Even when building is not the right answer, however, there’s sometimes a missing piece of the puzzle, and so it’s wise to have people on your team that are either competent coders or capable and enthusiastic to write glue or interface code.

Getting into CI/CD, we really wanted to drive easy adoption of the pipeline and have as little manual configuration overhead for developers as possible, to the point that the repo is the single system of record for all aspects of the application, a la GitOps. CI was pretty easy, since we could adopt JobDSL to auto-manage Jenkins configuration. There wasn’t anything remotely like that for Spinnaker, however, and so we set about writing Foremast.

There again, maybe you really need the commercial versions of tools like Artifactory or GitLab. But maybe you don’t.

Coming Next: Summary.

This article originally appeared on Medium.